Exploring Continued Fractions#

Python objects of the ContinuedFraction class encapsulate a number of basic and interesting properties of simple continued fractions that can be easily explored.

Note

All references to continued fractions are to the simple forms. Support for non-simple, generalised continued fractions is planned to be included in future releases.

Elements and Orders#

The elements (or coefficients) of a (possibly infinite), simple continued fraction \([a_0;a_1,a_2\cdots]\) of a real number \(x\) include the head \(a_0 = [x]\), which is the integer part of \(x\), and the tail elements \(a_1,a_2,\cdots\) which occur in the denominators of the fractional terms. The elements property can be used to look at their elements, e.g. for ContinuedFraction(649, 200) we have:

>>> cf = ContinuedFraction(649, 200)

>>> cf.elements

(3, 4, 12, 4)

The order of a continued fraction is defined to be number of its elements after the first. Thus, for ContinuedFraction(649, 200) the order is 3:

>>> cf.order

3

All ContinuedFraction instances will have a finite sequence of elements and thus a finite order, even if mathematically the numbers they represent may be irrational. The integers represent the special case of zero-order continued fractions.

>> ContinuedFraction(3).order

0

The elements and orders of ContinuedFraction instances are well behaved with respect to all rational operations supported by

fractions.Fraction:

>>> ContinuedFraction(415, 93).elements

(4, 2, 6, 7)

>>> ContinuedFraction(649, 200) + ContinuedFraction(415, 93)

ContinuedFraction(143357, 18600)

>>> (ContinuedFraction(649, 200) + ContinuedFraction(415, 93)).elements

(7, 1, 2, 2, 2, 1, 1, 11, 1, 2, 12)

>>> (ContinuedFraction(649, 200) + ContinuedFraction(415, 93)).order

10

Convergents and Rational Approximations#

For an integer \(k >= 0\) the (simple) \(k\)-th convergent \(C_k\) of a simple continued fraction \([a_0; a_1,\ldots]\) of a real number \(x\) is the rational number \(\frac{p_k}{q_k}\) with the simple continued fraction \([a_0; a_1,\ldots,a_k]\) formed from the first \(k + 1\) elements of the original.

The ContinuedFraction provides a convergent() method to compute the \(k\)-order convergent for \(k=0,1,\ldots,n\), where \(n\) is the order of the continued fraction.

>>> cf = ContinuedFraction(649 200)

>>> cf.convergent(0), cf.convergent(1), cf.convergent(2), cf.convergent(3)

(ContinuedFraction(3, 1), ContinuedFraction(13, 4), ContinuedFraction(159, 49), ContinuedFraction(649, 200))

Using the simple continued fraction \([3; 4, 12, 4]\) of \(\frac{649}{200}\) we can verify that these convergents are mathematically correct.

Fast Algorithms for Computing Convergents#

Convergents have very important properties that are key to fast approximation algorithms. The first of these is a recurrence relation between the convergents given by:

where \(p_0 = a_0\), \(q_0 = 1\), \(p_1 = p_1p_0 + 1\), and \(q_1 = p_1\). This formula is faithfully implemented by the convergent() method, and is much faster than recursive implementations or even alternative iterative approaches involving repeated integer or fractions.Fraction division - the key is to avoid division completely, and this is exactly what the formula enables.

It is also possible to get all of the convergents at once using the cached convergents property:

>>> ContinuedFraction(649 200).convergents

mappingproxy({0: ContinuedFraction(3, 1),

1: ContinuedFraction(13, 4),

2: ContinuedFraction(159, 49),

3: ContinuedFraction(649, 200)})

The result is a types.MappingProxyType object, and is keyed by convergent order \(0, 1,\ldots, n\).

>>> cf = ContinuedFraction(649 200)

>>> cf.convergents[0], cf.convergents[2]

(ContinuedFraction(3, 1), ContinuedFraction(159, 49))

Unlike the convergent() method the convergents property is cached, and is thus much faster when needing to make repeated use of the convergents.

Even- and Odd-order Convergents#

It is known that even- and odd-order convergents behave differently: the even-order convergents \(C_0,C_2,C_4,\ldots\) strictly increase, while the odd-order convergents \(C_1,C_3,C_5,\ldots\) strictly decrease, both at a decreasing rate. This is captured by the formula:

The ContinuedFraction class provides (cached) properties for even-order convergents (even_order_convergents) and odd-order convergents (odd_order_convergents), as illustrated below.

>>> ContinuedFraction(649 200).even_order_convergents

mappingproxy({0: ContinuedFraction(3, 1), 2: ContinuedFraction(159, 49)})

>>> ContinuedFraction(649 200).odd_order_convergents

mappingproxy({1: ContinuedFraction(13, 4), 3: ContinuedFraction(649, 200)})

As with convergents the results are types.MappingProxyType objects, and are keyed by convergent order.

The different behaviour of even- and odd-order convergents can be illustrated by looking at them for a ContinuedFraction approximation of \(\sqrt{2}\) with \(100\) 2s in the tail:

# Increase the current context precision to 100 digits

>>> decimal.getcontext().prec = 100

#

# Construct an approximation for the square root of 2, with 100 2s in the tail

>>> cf = ContinuedFraction.from_elements(1, *([2] * 100))

>>> cf

>>> ContinuedFraction(228725309250740208744750893347264645481, 161733217200188571081311986634082331709)

>>> cf.as_decimal()

Decimal('1.414213562373095048801688724209698078569671875376948073176679737990732478462093522589829309077750929')

#

# Look at the differences between consecutive even-order convergents

>>> cf.even_order_convergents[2] - cf.even_order_convergents[0]

>>> ContinuedFraction(2, 5)

>>> cf.even_order_convergents[4] - cf.even_order_convergents[2]

>>> ContinuedFraction(2, 145)

>>> cf.even_order_convergents[6] - cf.even_order_convergents[4]

>>> ContinuedFraction(2, 4901)

>>> cf.even_order_convergents[8] - cf.even_order_convergents[6]

>>> ContinuedFraction(2, 166465)

>>> cf.even_order_convergents[10] - cf.even_order_convergents[8]

>>> ContinuedFraction(2, 5654885)

#

# Look at the differences between consecutive odd-order convergents

>>> cf.odd_order_convergents[3] - cf.odd_order_convergents[1]

>>> ContinuedFraction(-1, 12)

>>> cf.odd_order_convergents[5] - cf.odd_order_convergents[3]

>>> ContinuedFraction(-1, 420)

>>> cf.odd_order_convergents[7] - cf.odd_order_convergents[5]

>>> ContinuedFraction(-1, 14280)

>>> cf.odd_order_convergents[9] - cf.odd_order_convergents[7]

>>> ContinuedFraction(-1, 485112)

Rational Approximation#

Each convergent \(C_k\) is said to represent a rational approximation \(\frac{p_k}{q_k}\) of a real number, say, \(x\), to which the sequence \((C_k)\) converges. This is expressed formally by:

The current implementation of ContinuedFraction can only represent finite (simple) continued fractions, which means that the convergents in its instances will always be finite in number, regardless of whether the real numbers they approximate are rational or irrational. Support for infinite, generalised continued fractions will be added in future releases.

We know, for example, that the square root \(\sqrt{n}\) of any non-square (positive) integer \(n\) is irrational. This can be seen by writing \(n = a^2 + r\), for integers \(a, r > 0\), from which we have:

Expanding the expression for \(\sqrt{n}\) recursively we have the following infinite periodic continued fraction for \(\sqrt{n}\):

With \(a = r = 1\) we can represent \(\sqrt{2}\) as the continued fraction:

written more compactly as \([1; \bar{2}]\), where \(\bar{2}\) represents an infinite sequence \(2, 2, 2, \ldots\).

We can illustrate rational approximation with the from_elements() method by continuing the earlier example for \(\sqrt{2}\) but instead using by iteratively constructing more accurate continued fraction representations with higher-order convergents:

>>> ContinuedFraction.from_elements(1, 2).as_decimal()

>>> Decimal('1.5')

>>> ContinuedFraction.from_elements(1, 2, 2).as_decimal()

>>> Decimal('1.4')

>>> ContinuedFraction.from_elements(1, 2, 2, 2, 2).as_decimal()

>>> Decimal('1.413793103448275862068965517')

...

>>> ContinuedFraction.from_elements(1, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2, 2).as_decimal()

>>> Decimal('1.414213624894869638351555929')

With the 10th convergent of \(\sqrt{2}\) we have obtained an approximation that is accurate to \(6\) decimal places in the fractional part. We’d ideally like to have as few elements as possible in our ContinuedFraction approximation of \(\sqrt{2}\) for a desired level of accuracy, but this partly depends on how fast the partial, finite continued fractions represented by the chosen sequences of elements in our approximations are converging to the true value of \(\sqrt{2}\) - these partial, finite continued fractions in a given continued fraction are called convergents, and will be discussed in more detail later on.

If we use the 100th convergent (with \(101\) elements consisting of the integer part \(1\), plus a tail of 100 twos), we get more accurate results:

# Create a `ContinuedFraction` from the sequence 1, 2, 2, 2, ..., 2, with 100 2s in the tail

>>> sqrt2_100 = ContinuedFraction.from_elements(1, *[2] * 100)

ContinuedFraction(228725309250740208744750893347264645481, 161733217200188571081311986634082331709)

>>> sqrt2_100.elements

# -> (1, 2, 2, 2, ..., 2) where there are `100` 2s after the `1`

>>> sqrt2_100.as_decimal()

Decimal('1.414213562373095048801688724')

The decimal value of ContinuedFraction.from_elements(1, *[2] * 100) in this construction is now accurate up to 27 digits in the fractional part, but the decimal representation stops there. Why 27? Because the decimal library uses a default contextual precision of 28 digits, including the integer part. The decimal precision can be increased, and the accuracy of the “longer” approximation above can be compared, as follows:

# `decimal.Decimal.getcontext().prec` stores the current context precision

>>> import decimal

>>> decimal.getcontext().prec

28

# Increase it to 100 digits, and try again

>>> decimal.getcontext().prec = 100

>>> sqrt2_100 = ContinuedFraction.from_elements(1, *[2] * 100)

>>> sqrt2_100

ContinuedFraction(228725309250740208744750893347264645481, 161733217200188571081311986634082331709)

>>> sqrt2_100.as_decimal()

Decimal('1.414213562373095048801688724209698078569671875376948073176679737990732478462093522589829309077750929')

Now, the decimal value of ContinuedFraction.from_elements(1, *[2] * 100) is accurate up to 75 digits in the fractional part, but deviates from the true value after 76th digit onwards.

This example also highlights the fact that “almost all” square roots of positive integers are irrational, even though the set of positive integers which are perfect squares and the set of positive integers which are not perfect squares are both countably infinite - the former is an infinitely sparser subset of the integers.

Remainders#

The \(k\)-th remainder \(R_k\) of a simple continued fraction \([a_0; a_1,\ldots]\) is the simple continued fraction \([a_k;a_{k + 1},\ldots]\), obtained from the original by “removing” the elements of the \((k - 1)\)-st convergent \(C_{k - 1} := [a_0;a_1,\ldots,a_{k - 1}]\).

If \([a_0; a_1,\ldots]\) is of finite order then each \(R_k\) is a rational number. The remainders of ContinuedFraction instances can be obtained via the remainder() method, which takes a non-negative integer not exceeding the order of the original.

>>> cf.remainder(0), cf.remainder(1), cf.remainder(2), cf.remainder(3)

(ContinuedFraction(649, 200), ContinuedFraction(200, 49), ContinuedFraction(49, 4), ContinuedFraction(4, 1))

It is also possible to get all of the remainders at once using the cached remainders property:

>>> cf.remainders

mappingproxy({0: ContinuedFraction(649, 200),

1: ContinuedFraction(200, 49),

2: ContinuedFraction(49, 4),

3: ContinuedFraction(4, 1)})

The result is a types.MappingProxyType object, and is keyed by remainder index \(0, 1,\ldots, n\).

>>> cf.remainders[0], cf.remainders[2]

(ContinuedFraction(649, 200), ContinuedFraction(49, 4))

Unlike the remainder() method the remainders property is cached, and is thus much faster when needing to make repeated use of the remainders.

Using the simple continued fraction of \(\frac{649}{200}\) we can verify that these remainders are mathematically correct.

Given a (possibly infinite) continued fraction \([a_0; a_1, a_2,\ldots]\) the remainders \(R_1,R_2,\ldots\) satisfy the following relation:

where \(\frac{1}{R_k}\) is a symbolic expression for the number represented by the inverted simple continued fraction \([0; a_k, a_{k + 1},\ldots]\).

Khinchin Means & Khinchin’s Constant#

For a (possibly infinite) continued fraction \([a_0; a_1, a_2,\ldots]\) and a positive integer \(n\) we define its \(n\)-th Khinchin mean \(K_n\) as the geometric mean of its first \(n\) elements starting from \(a_1\) (excluding the leading element \(a_0\)):

So \(K_n\) is simply the geometric mean of the integers \(a_1, a_2,\ldots,a_n\), for \(n \geq 1\).

It has been proved that for irrational numbers, which have infinite continued fractions, there are infinitely many for which the quantity \(K_n\) approaches a constant \(K_0 \approx 2.685452\ldots\), called Khinchin’s constant, independent of the number. So:

The ContinuedFraction class provides a way of examining the behaviour of \(K_n\) via the khinchin_mean property, as indicated in the examples below.

>>> ContinuedFraction(649, 200).elements

(3, 4, 12, 4)

>>> ContinuedFraction(649, 200).khinchin_mean

Decimal('5.76899828122963409526846589869819581508636474609375')

>>> ContinuedFraction(415, 93).elements

(4, 2, 6, 7)

>>> ContinuedFraction(415, 93).khinchin_mean

Decimal('4.37951913988788898990378584130667150020599365234375')

>>> (ContinuedFraction(649, 200) + ContinuedFraction(415, 93)).elements

(7, 1, 2, 2, 2, 1, 1, 11, 1, 2, 12)

>>> (ContinuedFraction(649, 200) + ContinuedFraction(415, 93)).khinchin_mean

Decimal('2.15015313349074244086978069390170276165008544921875')

>>> ContinuedFraction(5000).khinchin_mean

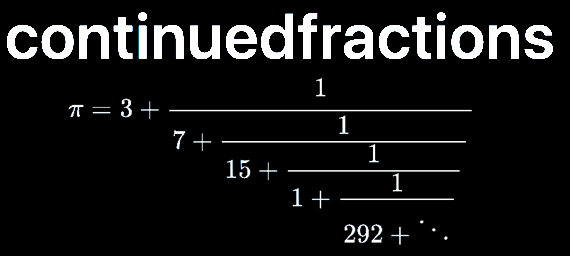

For rational numbers, which have finite continued fractions, the Khinchin means are not defined for all \(n\), so this property is not all that useful for rationals. However, for approximations of irrationals the property is useful as given in the examples below using continued fraction approximations for \(\pi = [3; 7, 15, 1, 292, \ldots]\).

# 4th Khinchin mean for `\pi` using a 5-element continued fraction approximation

>>> ContinuedFraction.from_elements(3, 7, 15, 1, 292).khinchin_mean

Decimal('13.2325345812843568893413248588331043720245361328125')

# 19th Khinchin mean for `\pi` using a 20-element continued fraction approximation

>>> ContinuedFraction.from_elements(3, 7, 15, 1, 292, 1, 1, 1, 2, 1, 3, 1, 14, 2, 1, 1, 2, 2, 2, 2).khinchin_mean

Decimal('2.60994679070748158977721686824224889278411865234375')

and \(\gamma = [0; 1, 1, 2, 1,\ldots]\), the Euler-Mascheroni constant:

# 4th Khinchin mean for `\gamma` using a 5-element continued fraction approximation

>>> ContinuedFraction.from_elements(0, 1, 1, 2, 1).khinchin_mean

Decimal('1.4422495703074085238171164746745489537715911865234375')

# 19th Khinchin mean for `\gamma` using a 20-element continued fraction approximation

>>> ContinuedFraction.from_elements(0, 1, 1, 2, 1, 2, 1, 4, 3, 13, 5, 1, 1, 8, 1, 2, 4, 1, 1, 40).khinchin_mean

Decimal('2.308255739839563336346373034757561981678009033203125')

The constant \(\gamma\), which has not been proved to be irrational, is defined as:

where \(H_n = \sum_{k=1}^n \frac1{k} = 1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{3} + \cdots \frac{1}{n}\) is the \(n\)-th harmonic number.

References#

[1] Baker, Alan. A concise introduction to the theory of numbers. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 2002.

[2] Barrow, John D. “Chaos in Numberland: The secret life of continued fractions.” plus.maths.org, 1 June 2000, https://plus.maths.org/content/chaos-numberland-secret-life-continued-fractionsURL.

[3] Emory University Math Center. “Continued Fractions.” The Department of Mathematics and Computer Science, https://mathcenter.oxford.emory.edu/site/math125/continuedFractions/. Accessed 19 Feb 2024.

[4] Khinchin, A. Ya. Continued Fractions. New York: Dover Publications, 1997.

[5] Python 3.12.2 Docs. “decimal - Decimal fixed point and floating point arithmetic.” https://docs.python.org/3/library/decimal.html. Accessed 21 February 2024.

[6] Python 3.12.2 Docs. “Floating Point Arithmetic: Issues and Limitations.” https://docs.python.org/3/tutorial/floatingpoint.html. Accessed 20 February 2024.

[7] Python 3.12.2 Docs. “fractions - Rational numbers.” https://docs.python.org/3/library/fractions.html. Accessed 21 February 2024.

[8] Wikipedia. “Continued Fraction”. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Continued_fraction. Accessed 19 February 2024.

[9] Wikipedia. “Euler’s constant”. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Euler%27s_constant. Accessed 11 March 2024.

[10] Wikipedia. “Khinchin’s constant”. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khinchin%27s_constant. Accessed 11 March 2024.